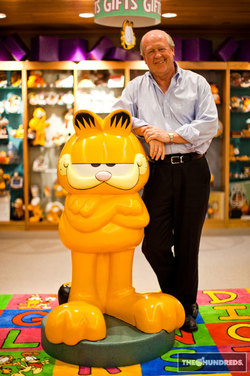

JIM DAVIS

Jim Davis was born July 28, 1945 in Marion, Indiana, and raised on a small farm with his parents, James and Betty Davis, and his younger brother, Dave (Doc). Like most farms, the barnyard had its share of stray cats; about 25 at one time, by Jim's estimation. As a child, he suffered serious bouts with asthma and was often bedridden. Forced inside, away from regular farm chores, he whiled away the hours drawing pictures.

Gnorm Gnat In college, he studied art and business before going to work for TUMBLEWEEDS creator, Tom Ryan. There, he learned the skills and discipline necessary to become a syndicated cartoonist and began his own strip, GNORM GNAT. When he tried to sell the strip to a newspaper syndicate he was told, "It's funny, but bugs? Who can relate to a bug?" After five years of GNORM, Davis crushed the bug strip idea and tried a new tact, studying the comics pages closely. He noticed there were a lot of successful strips about dogs, but none about cats! Combining his wry wit with the art skills he had honed since childhood, GARFIELD, a fat, lazy, lasagna loving, cynical cat was born. Davis says Garfield is a composite of all the cats he remembered from his childhood, rolled into one feisty orange fur ball. Garfield was named after his grandfather, James Garfield Davis.

Garfield first appeared in June 19, 1978 The strip debuted on June 19, 1978 in 41 U.S. newspapers. Several months after the launch, the Chicago Sun-Times cancelled GARFIELD. Over 1300 angry readers demanded that GARFIELD be reinstated. It was, and the rest, as they say, is history. Today, GARFIELD is read in over 2100 newspapers by 200 million people. Guinness World Records™, named GARFIELD “The Most Widely Syndicated Comic Strip in the World.” Davis’s peers at the National Cartoonist Society honored him with Best Humor Strip (1981 and 1985), the Elzie Segar Award (1990), and the coveted Reuben Award (1990), the top award presented to a cartoonist by NCS members.

Garfield quickly became a sensation in the licensing world, too, inspiring Davis to form his own company to take care of Garfield business concerns. Paws, Inc., founded in 1981, manages the worldwide rights for the famous fat cat, and Davis serves as President.

Jim has won four Emmy Awards Garfield’s fame spilled over to television and Davis penned eleven primetime specials for CBS-TV. He received ten Emmy nominations and four Emmy Awards for Outstanding Animated Program. Movies were next, and Twentieth Century Fox turned out Garfield: The Movie (‘04), and Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties (‘06). Davis also wrote the original screenplays and executive produced three animated features for DVD: Garfield Gets Real (‘07), Garfield’s Fun Fest (‘08), and Garfield’s Pet Force (‘09). Also in 2009. “The Garfield Show” made its debut on Cartoon Network. Today, the CGI animated cartoon is in its fourth season and is seen in 131 countries, including China, where CCTV broadcasts the show daily.

Davis’s philanthropy has been directed at educational and environmental projects. He founded The Professor Garfield Foundation in cooperation with Ball State University, to support children’s literacy. A free educational web site www.professorgarfield.org is the cornerstone of the Foundation’s work to date. Davis spearheaded reforestation, prairie and wetlands restorations, and built the world’s first all natural wastewater plant for commercial use. He was awarded the National Arbor Day Foundation’s Good Steward and Special Projects Award, and the Indiana Wildlife Federations’ Conservationist of the Year Award.

Davis spends his leisure time golfing, gardening, fishing, and enjoying his wife, children, and grandchildren. In a nod to Garfield’s friends in the comic strip, Davis also keeps one cat, Nermal, and a dog, Pooky.

Jim Davis was born July 28, 1945 in Marion, Indiana, and raised on a small farm with his parents, James and Betty Davis, and his younger brother, Dave (Doc). Like most farms, the barnyard had its share of stray cats; about 25 at one time, by Jim's estimation. As a child, he suffered serious bouts with asthma and was often bedridden. Forced inside, away from regular farm chores, he whiled away the hours drawing pictures.

Gnorm Gnat In college, he studied art and business before going to work for TUMBLEWEEDS creator, Tom Ryan. There, he learned the skills and discipline necessary to become a syndicated cartoonist and began his own strip, GNORM GNAT. When he tried to sell the strip to a newspaper syndicate he was told, "It's funny, but bugs? Who can relate to a bug?" After five years of GNORM, Davis crushed the bug strip idea and tried a new tact, studying the comics pages closely. He noticed there were a lot of successful strips about dogs, but none about cats! Combining his wry wit with the art skills he had honed since childhood, GARFIELD, a fat, lazy, lasagna loving, cynical cat was born. Davis says Garfield is a composite of all the cats he remembered from his childhood, rolled into one feisty orange fur ball. Garfield was named after his grandfather, James Garfield Davis.

Garfield first appeared in June 19, 1978 The strip debuted on June 19, 1978 in 41 U.S. newspapers. Several months after the launch, the Chicago Sun-Times cancelled GARFIELD. Over 1300 angry readers demanded that GARFIELD be reinstated. It was, and the rest, as they say, is history. Today, GARFIELD is read in over 2100 newspapers by 200 million people. Guinness World Records™, named GARFIELD “The Most Widely Syndicated Comic Strip in the World.” Davis’s peers at the National Cartoonist Society honored him with Best Humor Strip (1981 and 1985), the Elzie Segar Award (1990), and the coveted Reuben Award (1990), the top award presented to a cartoonist by NCS members.

Garfield quickly became a sensation in the licensing world, too, inspiring Davis to form his own company to take care of Garfield business concerns. Paws, Inc., founded in 1981, manages the worldwide rights for the famous fat cat, and Davis serves as President.

Jim has won four Emmy Awards Garfield’s fame spilled over to television and Davis penned eleven primetime specials for CBS-TV. He received ten Emmy nominations and four Emmy Awards for Outstanding Animated Program. Movies were next, and Twentieth Century Fox turned out Garfield: The Movie (‘04), and Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties (‘06). Davis also wrote the original screenplays and executive produced three animated features for DVD: Garfield Gets Real (‘07), Garfield’s Fun Fest (‘08), and Garfield’s Pet Force (‘09). Also in 2009. “The Garfield Show” made its debut on Cartoon Network. Today, the CGI animated cartoon is in its fourth season and is seen in 131 countries, including China, where CCTV broadcasts the show daily.

Davis’s philanthropy has been directed at educational and environmental projects. He founded The Professor Garfield Foundation in cooperation with Ball State University, to support children’s literacy. A free educational web site www.professorgarfield.org is the cornerstone of the Foundation’s work to date. Davis spearheaded reforestation, prairie and wetlands restorations, and built the world’s first all natural wastewater plant for commercial use. He was awarded the National Arbor Day Foundation’s Good Steward and Special Projects Award, and the Indiana Wildlife Federations’ Conservationist of the Year Award.

Davis spends his leisure time golfing, gardening, fishing, and enjoying his wife, children, and grandchildren. In a nod to Garfield’s friends in the comic strip, Davis also keeps one cat, Nermal, and a dog, Pooky.

OLIVE RUSH

Olive Rush was born in Fairmount, Indiana in 1875 to a Quaker farm family of six children, and attended nearby Earlham College, a Quaker school with a studio art program. Encouraged by her teacher, Rush enrolled in the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. in 1890, where she stayed for two years and achieved early recognition for her work. In 1893, Rush joined the Indiana delegation of artists to the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

In 1894, she moved to New York City and continued her studies at the Art Students League with Henry Siddons Mowbray, John Twachtman, and Augustus St. Gaudens. She secured her first job as an illustrator with Harper and Brothers and quickly started doing additional illustration work for Good Housekeeping, Scribner's, The Delineator, Woman's Home Companion, Sunday Magazine, and St. Nicholas Magazine. Rush also became a staff artist at the New York Tribune and illustrated several books.

In 1904, Rush sent an inquiry with samples of her work to master illustrator Howard Pyle, who had established what was then the only school of illustration in the country in Wilmington, Delaware. There he provided free instruction to a small number hand-picked artists culled from hundreds of applicants. Although Pyle did not admit women to his studio, he encouranged her to come and join the class for lectures and criticisms. Rush moved to Delaware later that year, joining a growing number of female illustrators there including Ethel Pennewill Brown (later Leach), Blanche Chloe Grant, Sarah Katherine Smith, and Harriet Roosevelt Richards, among others. Rush and her female colleagues lived together in a boarding house known as Tusculum, which became well-known as a gathering place for women artists.

Rush traveled to Europe in 1910, embarking on a period of intense study and travel which would mark a steady transition from illustration to painting. She studied at Newlyn in Cornwall, England and then in France with the American impressionist Richard E. Miller. She returned to Wilmington in 1911, where she moved into Pyle's studio with Ethel Pennewill Brown. Rush bounced to New York, Boston, and back to France, where she lived for a time with fellow artists Alice Schille, Ethel Pennewill Brown, and Orville Houghton Peets. Her reputation grew, and she began to exhibit regularly in major national and regional juried exhibitions including the Carnegie, Pennsylvania Academy, and Corcoran annual exhibitions, as well as the Hoosier Salon.

In 1914, Rush made her first trip to Arizona and New Mexico. Passing through Santa Fe on her return trip, Rush made contact with the artists community at the Museum of New Mexico, where she secured an impromptu solo exhibition after showing her new work, inspired by the landscape of the Southwest. She made Santa Fe her permanent home in 1920 in an adobe cottage on Canyon Road, which became a main thoroughfare of the Santa Fe artists' community.

Rush began to experiment with fresco painting, and developed her own techniques suitable to the local climate. She became a sought-after muralist and was asked to create frescoes for many private homes and businesses. In her painting, she often depicted the Native American dances and ceremonies she attended. She exhibited these paintings around the country, including with the Society of Independent Artists in New York, and in the Corcoran Annual Juried exhibition, where Mrs. Herbert Hoover and Duncan Phillips both purchased her work.

In 1932, Rush was hired to teach at the Santa Fe Indian School. Rush's enthusiastic work in the 1930s with the young pueblo artists is credited with helping to bring about a flourishing of Native American visual art in New Mexico. Rush continued to work with native artists throughout her life, and many of her associates went on to gain national reputations, including Harrison Begay, Awa-Tsireh, Pop Chalee, Pablita Valerde, and Ha-So-De (Narciso Abeyta).

From 1934 to 1939, Rush executed murals for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Rush's federal art projects included murals for the Santa Fe Public Library (1934), the Biology Building of the New Mexico Agricultural College (1935), the Pawhuska, Oklahoma Post Office (1938), and the Florence, Colorado Post Office (1939). Rush was also asked to join the Advisory Committee on Indian Art created by the PWAP in 1934, to help administer a segment of the program aimed at employing Native American artists.

In her later years, Rush's artwork became increasingly experimental, incorporating the ideas of Chinese painting, Native American art, and her contemporaries, the modernists, especially Wassily Kandinsky. She continued painting and exhibiting until 1964, when illness prohibited her from working. She died in 1966, leaving her home and studio to the Santa Fe Society of Friends.

Sources consulted for this biography include Olive Rush: A Hoosier Artist in New Mexico (1992) by Stanley L. Cuba, and Almost Forgotten: Delaware Women Artists and Arts Patrons 1900-1950 (2002) by Janice Haynes Gilmore.

Olive Rush was born in Fairmount, Indiana in 1875 to a Quaker farm family of six children, and attended nearby Earlham College, a Quaker school with a studio art program. Encouraged by her teacher, Rush enrolled in the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. in 1890, where she stayed for two years and achieved early recognition for her work. In 1893, Rush joined the Indiana delegation of artists to the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

In 1894, she moved to New York City and continued her studies at the Art Students League with Henry Siddons Mowbray, John Twachtman, and Augustus St. Gaudens. She secured her first job as an illustrator with Harper and Brothers and quickly started doing additional illustration work for Good Housekeeping, Scribner's, The Delineator, Woman's Home Companion, Sunday Magazine, and St. Nicholas Magazine. Rush also became a staff artist at the New York Tribune and illustrated several books.

In 1904, Rush sent an inquiry with samples of her work to master illustrator Howard Pyle, who had established what was then the only school of illustration in the country in Wilmington, Delaware. There he provided free instruction to a small number hand-picked artists culled from hundreds of applicants. Although Pyle did not admit women to his studio, he encouranged her to come and join the class for lectures and criticisms. Rush moved to Delaware later that year, joining a growing number of female illustrators there including Ethel Pennewill Brown (later Leach), Blanche Chloe Grant, Sarah Katherine Smith, and Harriet Roosevelt Richards, among others. Rush and her female colleagues lived together in a boarding house known as Tusculum, which became well-known as a gathering place for women artists.

Rush traveled to Europe in 1910, embarking on a period of intense study and travel which would mark a steady transition from illustration to painting. She studied at Newlyn in Cornwall, England and then in France with the American impressionist Richard E. Miller. She returned to Wilmington in 1911, where she moved into Pyle's studio with Ethel Pennewill Brown. Rush bounced to New York, Boston, and back to France, where she lived for a time with fellow artists Alice Schille, Ethel Pennewill Brown, and Orville Houghton Peets. Her reputation grew, and she began to exhibit regularly in major national and regional juried exhibitions including the Carnegie, Pennsylvania Academy, and Corcoran annual exhibitions, as well as the Hoosier Salon.

In 1914, Rush made her first trip to Arizona and New Mexico. Passing through Santa Fe on her return trip, Rush made contact with the artists community at the Museum of New Mexico, where she secured an impromptu solo exhibition after showing her new work, inspired by the landscape of the Southwest. She made Santa Fe her permanent home in 1920 in an adobe cottage on Canyon Road, which became a main thoroughfare of the Santa Fe artists' community.

Rush began to experiment with fresco painting, and developed her own techniques suitable to the local climate. She became a sought-after muralist and was asked to create frescoes for many private homes and businesses. In her painting, she often depicted the Native American dances and ceremonies she attended. She exhibited these paintings around the country, including with the Society of Independent Artists in New York, and in the Corcoran Annual Juried exhibition, where Mrs. Herbert Hoover and Duncan Phillips both purchased her work.

In 1932, Rush was hired to teach at the Santa Fe Indian School. Rush's enthusiastic work in the 1930s with the young pueblo artists is credited with helping to bring about a flourishing of Native American visual art in New Mexico. Rush continued to work with native artists throughout her life, and many of her associates went on to gain national reputations, including Harrison Begay, Awa-Tsireh, Pop Chalee, Pablita Valerde, and Ha-So-De (Narciso Abeyta).

From 1934 to 1939, Rush executed murals for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Rush's federal art projects included murals for the Santa Fe Public Library (1934), the Biology Building of the New Mexico Agricultural College (1935), the Pawhuska, Oklahoma Post Office (1938), and the Florence, Colorado Post Office (1939). Rush was also asked to join the Advisory Committee on Indian Art created by the PWAP in 1934, to help administer a segment of the program aimed at employing Native American artists.

In her later years, Rush's artwork became increasingly experimental, incorporating the ideas of Chinese painting, Native American art, and her contemporaries, the modernists, especially Wassily Kandinsky. She continued painting and exhibiting until 1964, when illness prohibited her from working. She died in 1966, leaving her home and studio to the Santa Fe Society of Friends.

Sources consulted for this biography include Olive Rush: A Hoosier Artist in New Mexico (1992) by Stanley L. Cuba, and Almost Forgotten: Delaware Women Artists and Arts Patrons 1900-1950 (2002) by Janice Haynes Gilmore.

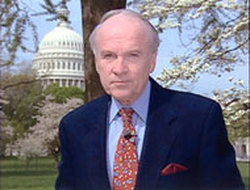

PHIL JONES

Phil Jones was a reporter-correspondent for CBS News for over three decades, reporting from Vietnam battlefields, covering presidential campaigns, the Watergate investigation, the Nixon resignation, and the impeachment trial of President Clinton. He was considered the dean of broadcast correspondents reporting on Congress when he covered that beat 1977-1989. Jones grew up in Fairmount, Indiana. While at Indiana University he was teamed with graduate student Dick Endberg on the new IU Sports Network broadcasts. His first fulltime news job was at WTHI-TV, Terre Haute. Jones later moved to WCCO-TV, Minneapolis, for 7 years, before joining CBS at its Atlanta bureau. He retired in 2001.

Phil Jones was a reporter-correspondent for CBS News for over three decades, reporting from Vietnam battlefields, covering presidential campaigns, the Watergate investigation, the Nixon resignation, and the impeachment trial of President Clinton. He was considered the dean of broadcast correspondents reporting on Congress when he covered that beat 1977-1989. Jones grew up in Fairmount, Indiana. While at Indiana University he was teamed with graduate student Dick Endberg on the new IU Sports Network broadcasts. His first fulltime news job was at WTHI-TV, Terre Haute. Jones later moved to WCCO-TV, Minneapolis, for 7 years, before joining CBS at its Atlanta bureau. He retired in 2001.

BOB SHEETS

Robert Chester Sheets (born June 7, 1937) is a meteorologist who served as the director of the National Hurricane Center from 1987 to 1995. He was born in Marion, Indiana and grew up in nearby Fairmount. He is well remembered for numerous interviews given from the Hurricane Center during Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Sheets also was a member and eventual director in Project Storm Fury, an attempt to modify hurricanes with silver iodide. Since retiring in 1995, Sheets has continued his relationship with the media, becoming a special-situation hurricane analyst with ABC network affiliates in Florida. He has also co-authored a book on hurricane information and stories.

Robert Chester Sheets (born June 7, 1937) is a meteorologist who served as the director of the National Hurricane Center from 1987 to 1995. He was born in Marion, Indiana and grew up in nearby Fairmount. He is well remembered for numerous interviews given from the Hurricane Center during Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Sheets also was a member and eventual director in Project Storm Fury, an attempt to modify hurricanes with silver iodide. Since retiring in 1995, Sheets has continued his relationship with the media, becoming a special-situation hurricane analyst with ABC network affiliates in Florida. He has also co-authored a book on hurricane information and stories.

MARY JANE WARD

Mary Jane Ward was born August 27, 1905 in Fairmount, Indiana. Ward - cousin of Ross Lockridge, Jr. - maintained an interest in writing and music from an early age; as a teenager, she composed her own music, but would eventually choose writing as her main focus. After graduating high school, Ward studied at Northwestern University and at Chicago's Lyceum of Arts Conservatory, and went on to work at a series of odd jobs. In March 1928 she married Edward Quayle, a statistician and amateur playwright, and became inspired to submit her own writing for publication. Ward published a few short stories, and in 1937 she received a job as a book reviewer for the Evanston News-Index. That same year, E. P. Dutton published Ward’s novel The Tree Has Roots. A second novel, The Wax Apple, was published in 1938. Both books received decent reviews but did not achieve much popularity.[3]

Ward and Quayle moved to Greenwich Village in 1939. Neither of them were very successful in publishing their material, and the financial stress eventually proved to be too much for Ward, who suffered a nervous breakdown and ended up spending more than eight months at Rockland State Hospital in Orangeburg, New York. Ward was (probably erroneously) diagnosed with schizophrenia. Her therapy included scalding baths and electroshock. Over the next few years, drawing from her experiences at the psychiatric institution, Ward penned the novel The Snake Pit. The book was published in 1946 and received glowing reviews from critics and from experts in the psychiatric field.

At the time The Snake Pit was released, Ward denied that the story reflected in any way on her own life, but it was later revealed that the book had been formed around her experiences at Rockland. The kindly character “Dr. Kik” is apparently based on Gerard Chrzanowski, who treated Ward at Rockland and was one of the first doctors in the U.S. to use psychoanalysis to treat patients with schizophrenia. Dr. Militades Zaphiropoulos, who also worked at Rockland while Ward was being treated there, stated in an interview that Chrzanowski was nicknamed “Dr. Kik” because Americans tended to have difficulty pronouncing his name.[4]

After the success of The Snake Pit, Ward and Quayle moved to a dairy farm outside of Chicago, where Ward continued to write. She went on to publish The Professor’s Umbrella (1948), A Little Night Music (1951), It’s Different for a Woman (1952),Counterclockwise (1969), and The Other Caroline (1970).

Ward was hospitalized for psychiatric issues three more times during her lifetime, and her last two novels revisit the theme of psychiatric illness. She died on February 17, 1981, in Tucson, Arizona, at the age of 75.

Mary Jane Ward was born August 27, 1905 in Fairmount, Indiana. Ward - cousin of Ross Lockridge, Jr. - maintained an interest in writing and music from an early age; as a teenager, she composed her own music, but would eventually choose writing as her main focus. After graduating high school, Ward studied at Northwestern University and at Chicago's Lyceum of Arts Conservatory, and went on to work at a series of odd jobs. In March 1928 she married Edward Quayle, a statistician and amateur playwright, and became inspired to submit her own writing for publication. Ward published a few short stories, and in 1937 she received a job as a book reviewer for the Evanston News-Index. That same year, E. P. Dutton published Ward’s novel The Tree Has Roots. A second novel, The Wax Apple, was published in 1938. Both books received decent reviews but did not achieve much popularity.[3]

Ward and Quayle moved to Greenwich Village in 1939. Neither of them were very successful in publishing their material, and the financial stress eventually proved to be too much for Ward, who suffered a nervous breakdown and ended up spending more than eight months at Rockland State Hospital in Orangeburg, New York. Ward was (probably erroneously) diagnosed with schizophrenia. Her therapy included scalding baths and electroshock. Over the next few years, drawing from her experiences at the psychiatric institution, Ward penned the novel The Snake Pit. The book was published in 1946 and received glowing reviews from critics and from experts in the psychiatric field.

At the time The Snake Pit was released, Ward denied that the story reflected in any way on her own life, but it was later revealed that the book had been formed around her experiences at Rockland. The kindly character “Dr. Kik” is apparently based on Gerard Chrzanowski, who treated Ward at Rockland and was one of the first doctors in the U.S. to use psychoanalysis to treat patients with schizophrenia. Dr. Militades Zaphiropoulos, who also worked at Rockland while Ward was being treated there, stated in an interview that Chrzanowski was nicknamed “Dr. Kik” because Americans tended to have difficulty pronouncing his name.[4]

After the success of The Snake Pit, Ward and Quayle moved to a dairy farm outside of Chicago, where Ward continued to write. She went on to publish The Professor’s Umbrella (1948), A Little Night Music (1951), It’s Different for a Woman (1952),Counterclockwise (1969), and The Other Caroline (1970).

Ward was hospitalized for psychiatric issues three more times during her lifetime, and her last two novels revisit the theme of psychiatric illness. She died on February 17, 1981, in Tucson, Arizona, at the age of 75.

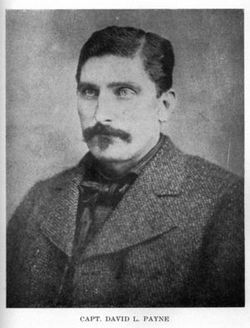

CAPTAIN DAVID LEWIS PAYNE

Early YearsDavid Lewis Payne was born on December 30, 1836 in Grant County, Indiana, on a farm near the small town of Fairmount. He was the son of William and Celia Lewis Payne. As a child Payne worked on his father’s farm and attended the local rural school during the winter months (Baldwin 209). In the spring of 1858, at the age of twenty–one, Payne and his brother, Jack, left home and began traveling west. Their hope was to eventually join the Mormon War but their intentions changed once they crossed the Missouri River. The brothers stopped in Burr Oak Township in Doniphan County, Kansas. There, Payne obtained a small portion of land on which he built a saw mill. The saw mill was not successful and Payne began to hunting to support himself. Soon after, Payne was hired by the government to scout for expeditions. This job would eventually lead to his exploration of the Oklahoma territory (Osburn 1).

Military and Political AccomplishmentsAt the beginning of the Civil War Payne enlisted in the 10th Kansas Volunteer Infantry. Because of his courageous conduct he was immediately promoted to captain. He served from August 1861 to August 1864. After his service Payne went back to Doniphan County and was elected to the Kansas Legislature, where he served in the 1864 and 1865 sessions (Osburn 2). In March of 1865 Payne enlisted for one year in the 15th Kansas Cavalry. This particular unit was brought up in response to a state legislative resolution calling for the governor to organize a regiment of veteran volunteers to protect western Kansas from Indian activity (Warr 214). In July of 1867, Governor Crawford issued a public statement calling for volunteers to protect the Kansas people from Indian attacks. As a result, the 18th Kansas Cavalry was set up. Payne enlisted with the cavalry and proceeded to serve his duties. In 1868 Payne once again enlisted into the service, this time with the 19th Kansas Cavalry. This regiment was organized in October 1868 to serve in a winter operation against Indians on the Western Plains. Payne then moved to Sedgwick County, Kansas where he was again elected as Senator to the State Legislature (Osburn 2). Payne’s experiences and contributions in politics eventually led to his appointments as Postmaster at Fort Leavenworth on March 19, 1867. Payne also had the honor of being the Assistant to the Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives (Davis 146).

Oklahoma TerritoryIn 1881, Captain Payne got an idea of starting stimulation for the opening of the Oklahoma Territory. He began formulating bills that he sent out describing his purpose to open Oklahoma for settlement. In his bills Payne stated he would locate parties on the land, and form a stock company to finance the necessary funds that would be needed to follow through with the operation. Shares for the stock sold for five dollars each. About three thousand different investors became apart of Payne’s plan and in 1883, Payne and the stockholders moved into the Territory (Baldwin 212). There Payne and his party laid out a town that was named Ewing. The fourth cavalry soon arrested Payne and his party for their actions of trying to settle. Payne and his team were taken to Ft. Reno, and then were later escorted back to Kansas and freed. Payne was enraged because as stated by public law the military were prohibited from interfering in civil matters. Payne and a larger party returned to Ewing in July (Captain David 5). The cavalry yet again arrested the party and escorted them back to Kansas. Once more Payne was freed but was forced to appear in court in Ft. Smith, Arkansas. There, Payne was charged under the Intercourse Act. He was fined one thousand dollars, but since he had no money or property, the fines were dropped (Osburn 3). During his expedition into the Cherokee Outlet in 1884, Payne was once again arrested by the army. Instead of returning him to Kansas, he was taken several hundred miles, under grueling physical conditions, to Ft. Smith. He was then turned over to the United States District Court in Topeka, Kansas. Judge Cassius G. Foster repealed his indictments and ruled that settling on the Unassigned Lands was not a criminal offense. Boomers celebrated the verdict but then were soon shot down when the government refused to accept the decision. Payne finally planned another expedition, but this would be his last. On the morning of November 28, 1884, in Wellington, Kansas David Payne collapsed and died at his breakfast table. His funeral at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Wellington filled with thousands of his followers and family. The Boomer movement could not be stopped though. Within days of his death, Congress introduced a bill for the purpose of authorizing the opening of the Oklahoma settlement (Captain David 5).

Conclusion

Tomb

In 1995 Payne’s family, after trying for almost a century, was able to have his remains moved to Oklahoma. On April 22, 1995 a monument was built to dedicate David Lewis Payne (Appendix B). His final resting place is in the park overlooking Boomer Lake in Stillwater, Payne County, Oklahoma (Osburn 3). David Lewis Payne’s accomplishments, politically and militaristically, are still sought today as something amazing. His efforts and determination showed American people that one person can make a difference.

Early YearsDavid Lewis Payne was born on December 30, 1836 in Grant County, Indiana, on a farm near the small town of Fairmount. He was the son of William and Celia Lewis Payne. As a child Payne worked on his father’s farm and attended the local rural school during the winter months (Baldwin 209). In the spring of 1858, at the age of twenty–one, Payne and his brother, Jack, left home and began traveling west. Their hope was to eventually join the Mormon War but their intentions changed once they crossed the Missouri River. The brothers stopped in Burr Oak Township in Doniphan County, Kansas. There, Payne obtained a small portion of land on which he built a saw mill. The saw mill was not successful and Payne began to hunting to support himself. Soon after, Payne was hired by the government to scout for expeditions. This job would eventually lead to his exploration of the Oklahoma territory (Osburn 1).

Military and Political AccomplishmentsAt the beginning of the Civil War Payne enlisted in the 10th Kansas Volunteer Infantry. Because of his courageous conduct he was immediately promoted to captain. He served from August 1861 to August 1864. After his service Payne went back to Doniphan County and was elected to the Kansas Legislature, where he served in the 1864 and 1865 sessions (Osburn 2). In March of 1865 Payne enlisted for one year in the 15th Kansas Cavalry. This particular unit was brought up in response to a state legislative resolution calling for the governor to organize a regiment of veteran volunteers to protect western Kansas from Indian activity (Warr 214). In July of 1867, Governor Crawford issued a public statement calling for volunteers to protect the Kansas people from Indian attacks. As a result, the 18th Kansas Cavalry was set up. Payne enlisted with the cavalry and proceeded to serve his duties. In 1868 Payne once again enlisted into the service, this time with the 19th Kansas Cavalry. This regiment was organized in October 1868 to serve in a winter operation against Indians on the Western Plains. Payne then moved to Sedgwick County, Kansas where he was again elected as Senator to the State Legislature (Osburn 2). Payne’s experiences and contributions in politics eventually led to his appointments as Postmaster at Fort Leavenworth on March 19, 1867. Payne also had the honor of being the Assistant to the Doorkeeper of the United States House of Representatives (Davis 146).

Oklahoma TerritoryIn 1881, Captain Payne got an idea of starting stimulation for the opening of the Oklahoma Territory. He began formulating bills that he sent out describing his purpose to open Oklahoma for settlement. In his bills Payne stated he would locate parties on the land, and form a stock company to finance the necessary funds that would be needed to follow through with the operation. Shares for the stock sold for five dollars each. About three thousand different investors became apart of Payne’s plan and in 1883, Payne and the stockholders moved into the Territory (Baldwin 212). There Payne and his party laid out a town that was named Ewing. The fourth cavalry soon arrested Payne and his party for their actions of trying to settle. Payne and his team were taken to Ft. Reno, and then were later escorted back to Kansas and freed. Payne was enraged because as stated by public law the military were prohibited from interfering in civil matters. Payne and a larger party returned to Ewing in July (Captain David 5). The cavalry yet again arrested the party and escorted them back to Kansas. Once more Payne was freed but was forced to appear in court in Ft. Smith, Arkansas. There, Payne was charged under the Intercourse Act. He was fined one thousand dollars, but since he had no money or property, the fines were dropped (Osburn 3). During his expedition into the Cherokee Outlet in 1884, Payne was once again arrested by the army. Instead of returning him to Kansas, he was taken several hundred miles, under grueling physical conditions, to Ft. Smith. He was then turned over to the United States District Court in Topeka, Kansas. Judge Cassius G. Foster repealed his indictments and ruled that settling on the Unassigned Lands was not a criminal offense. Boomers celebrated the verdict but then were soon shot down when the government refused to accept the decision. Payne finally planned another expedition, but this would be his last. On the morning of November 28, 1884, in Wellington, Kansas David Payne collapsed and died at his breakfast table. His funeral at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Wellington filled with thousands of his followers and family. The Boomer movement could not be stopped though. Within days of his death, Congress introduced a bill for the purpose of authorizing the opening of the Oklahoma settlement (Captain David 5).

Conclusion

Tomb

In 1995 Payne’s family, after trying for almost a century, was able to have his remains moved to Oklahoma. On April 22, 1995 a monument was built to dedicate David Lewis Payne (Appendix B). His final resting place is in the park overlooking Boomer Lake in Stillwater, Payne County, Oklahoma (Osburn 3). David Lewis Payne’s accomplishments, politically and militaristically, are still sought today as something amazing. His efforts and determination showed American people that one person can make a difference.